Brian K. Vaughan and Steve Skroce’s new ongoing series, We Stand on Guard (Image Comics), centers on a 22nd-century American invasion of Canada, and the Canadian guerillas (the Two-Four, named after the Canadian slang term for a 24 case of beer) and American soldiers caught up in the conflict. But while the first three issues of the series have not flinched from the brutalities of war on both sides—including war crimes such as summary executions and torture—one senses this is not ultimately a story about war, but rather about national identity. In essence, Vaughan and Skroce are asking what it is that makes Canadians and Americans different. (Thus far, this question has been explored from the Canadian perspective, though I anticipate as the series continues Vaughan and Skroce will explore the American invaders in greater depth.)

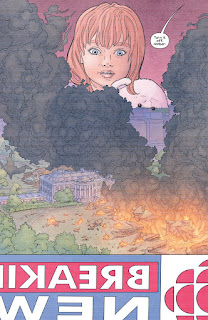

From its very first panel, it is clear that We Stand on Guard will be steeped in imagery wrought with Canadian nationalist implications. Above the logo of the CBC (the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), Skroce illustrates the White House not merely in ruins, but actually on fire, evoking the historical Burning of Washington in 1814. The connection is made overt over the next several pages, as readers learn first that the year is 2112—the tercentennial of the War of 1812—and then Tommy, older brother of the central protagonist Amber, suggests it was Canadians who did it, since they had done it before, “Like, three hundred years ago.”

Though his father quibbles with the details—it had been British, not Canadian, soldiers who actually set fire to the White House—the incident and the entire War of 1812 remains a pivotal moment in Canadian national identity. When the war began, American politicians widely predicted an easy victory and quick annexation of the Canadas, and many predicted the population of Upper Canada (now Ontario) to greet American troops at liberators (a claim all-too-common in American military discourse). That Americans could not conquer a sparsely defended territory on its own borders became a great embarrassment (such that it is now rarely discussed in American political discourse, with what little attention paid to the War of 1812 instead focused on Francis Scott Key in the Battle of Baltimore and Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans). But, in Canada, the war took on greater meaning—it was the time that disparate, disorganized settlers joined together to form a new nation, one that would be largely defined in opposition to the United States. By evoking the War of 1812, Vaughan and Skroce present the Canadian cause as not merely just, but also as potentially winnable.

Canadian identity is also reinforced in more subtle ways throughout the series, through references and gags immediately recognizable to a Canadian audience, but likely to be missed by most Americans. In the first issue, for instance, a Tim Horton’s franchise can be seen out of Amber’s window in Ottawa. While the chain operates some stores in the United States, it is omnipresent in Canada and, per Joe Friesen of The Globe and Mail, “It has insinuated itself into the Canadian identity with such remarkable success that for some it has become enmeshed in the very idea of Canadianness.”

Before opening his eponymous coffee shop, however, Tim Horton was first that most revered of Canadian figures: a hockey player. Though Canada’s claims to have invented hockey are contested, and the sport is also beloved across significant swathes of Europe, it is by far the most popular amateur and professional sport in Canada. More importantly, Canadians see their love of hockey as one of the things that differentiate them from Americans. In We Stand on Guard, knowledge of hockey becomes a shorthand for Canadianness—skeptical that Amber might be an American spy, Dunn asks her, “If you’re really one of us, who took home the last [Stanley] Cup in ‘11?”. Amber’s response—”I have no idea. I don’t even like hockey. And I was fucking five,”—is the series’ first contestation of a unified Canadian identity.

While Canadians do point to certain shared institutions—including hockey, Tim Horton’s, and the CBC—as defining Canadianness, Canadian national identity is more often expressed as a negative: Canada is not the United States. While Canada is not alone in having nationalized health insurance, it is the only state to consider that a major part of its national identity, something that only makes sense in comparison to Canada’s uncaring, capitalist southern neighbor. More recently, Canadians have seen themselves as the defenders of human rights and the international system, in strict opposition to perceptions of American warmongering and torture. Thus far in We Stand on Guard, the Americans fall precisely into the Canadian narrative: imperialists determined to control a strategic resource—here water, rather than oil—through brutal occupation justified by a possibly intentional misreading of geopolitical events.

But, while the Canadians of We Stand on Guard seem to be in the right—there is no evidence yet to suggest that the destruction of the White House really was a Canadian plot or that the American invasion is anything but a grab for resources—it is not clear that the members of the Two-Four are really that different from their American counterparts. When Highway suggests an American captive might have useful information, McFadden replies “Torture hasn’t worked for us yet.” The crucial difference between Canadians and Americans isn’t that the first rejects torture outright, but that it recognizes the dubious value of information obtained from it. Yet, two issues later, when McFadden is herself subjected to torture, she ultimately gives up the precise location of the Two-Four’s secret base. Perhaps the real difference is that Americans are more brutal with their torture; having prisoners virtually raped by their fathers certainly seems outside the realm of what the Two-Four would have been capable of, both on a technological and emotional level. More importantly, it is the Two-Four, not the American invaders, who commit the first war crime portrayed in the series: the execution of an American prisoner, despite his overt surrender and reference to his rights under international law. Far from being the protectors of international human rights, the Canadians are just war criminals on a smaller scale.

Similar questions could also be raised about many of the other symbols of Canadian national identity shown by Vaughan and Skroce. Booth may be onto something when he compares Canada to Krypton, but Amber is not wrong when she questions his adoration of the “guy who fights for truth, justice and the American fucking way.” (It is also difficult to take Booth’s argument seriously after the rise and fall of former Liberal Party of Canada leader Michael Ignatieff, whose career was fatally hampered by his decades spent outside of Canada.)

Tim Horton’s might be as Canadian as poutine, but its recent merger with Burger King raises some doubts about whether that status will continue indefinitely. Even hockey has seen a fall in ratings (if not yet prestige) since the NHL sold broadcast rights to Rogers Communications, rather than the CBC, the traditional home of Hockey Night in Canada. We Stand Our Guard presents a view of Canadian identity that is at once immediately recognizable to an early 21st-century audience (down to the use of contemporary logos that are certain to change over the next century), while also fraught with uncertainty.

It is, of course, unwise to draw too many conclusions from the first three issues—not even the first full arc!—of an ongoing series. It remains to be seen whether Vaughan and Skroce will highlight the Two-Four as heroes against the invading Yanks or present a more nuanced “neither side is really better than the other” view. Either way, however, it is likely that the discourse of Canadian national identity will remain at the forefront of the series, whether it ultimately reinforces or deconstructs it.